(… before it’s too late)

In early 1991 my interest was piqued by a newspaper column penned by Humberto Cruz. It was a new column that began running weekly titled “The Savings Game”.

Mr. Cruz planned to retire a millionaire in spite of a very ordinary middle-class income. It sounded audacious until I delved further into his commonsense advice. Cruz and Georgina (who he would later marry) were immigrants, having escaped Fidel Castro’s Cuba as teenagers in 1960 along with their parents.**

Fast forward to December of 2010 and Humberto signed off on his (final) 1,028th edition of “The Savings Game”. He and his wife were retiring having amassed a net worth of over 2 million dollars. In 2019 they were enjoying a Holland America Cruise around the world.

I read Mr. Cruz’s column religiously. It is impossible for me to recount every piece of advice that he gave over the decades, but there are some fundamentals, supplemented by other knowledge that I acquired over the years, that may serve to bring financial security to our children, grandchildren… and perhaps you as well.

Mr. Cruz’s last article offered the following:

“Over the course of 1,028 weekly columns… I have emphasized basic principles for financial success. They all entail personal responsibility:

-

- Spend less than you make.

- Save and invest the difference wisely for the goals most important to you.

- Identify those goals clearly. Calculate how much you have to save, and the investment returns you need so you don’t take more risks than necessary.

- Never forget that money is only a tool. True happiness comes from commitment and relationships, not material wealth.

All this is very simple but not necessarily easy to accomplish.”

Humberto Cruz. December 27, 2010

Over the years I subscribed to the magazine, “Better Investing”. It provided advice and tools for the average investor. Nothing exotic, just identify sound companies with long term stable histories of growth and invest in those companies, only selling when there was a sound financial reason. BI counseled that it was folly to try and time the market. Investing is not gambling. Invest in what you understand and understand why you invest. Invest for the long haul. A basic tenet was that a well selected portfolio of 5 stocks will typically have one loser, 3 average performers, and one overachiever. And that it is not unreasonable to set 15% as an average annual growth goal.

If one chooses not to be an active investor and “merely” invests in a mutual fund that tracks the Standard and Poor’s 500 index the average annual rate of return from 1950 to 2020 (roughly my lifetime) was 12.96%.

Moreover, index funds as are available from brokerage firms such as Fidelity Investments and Vanguard, offer “no-load” funds (there is no upfront cost to invest), and the annual expense ratio (fees) can be very low, two tenths of a percent (.2%) or less. (Caveat: No actual investment advice is intended here, UNDERSTAND and INVESTIGATE before you INVEST!!)

It is reputed that Albert Einstein once said, “Compound interest is the Eighth Wonder of the World”. To this he reportedly added, “…He who understands it, earns it… he who doesn’t, pays it.”

One may calculate how many years it takes for a sum of money to double based upon the compound interest rate. It is a simple formula; Divide 72 by the interest rate, the result is the answer in years. Applying this bit of information to the average annual growth of the stock market (S&P 500) from 1950 to 2020: 72 ÷ 12.96 = 5.5.

In other words, over those 70 years money in an investment that tracked the S&P 500 doubled every 5.5 years. Put in more concrete terms:

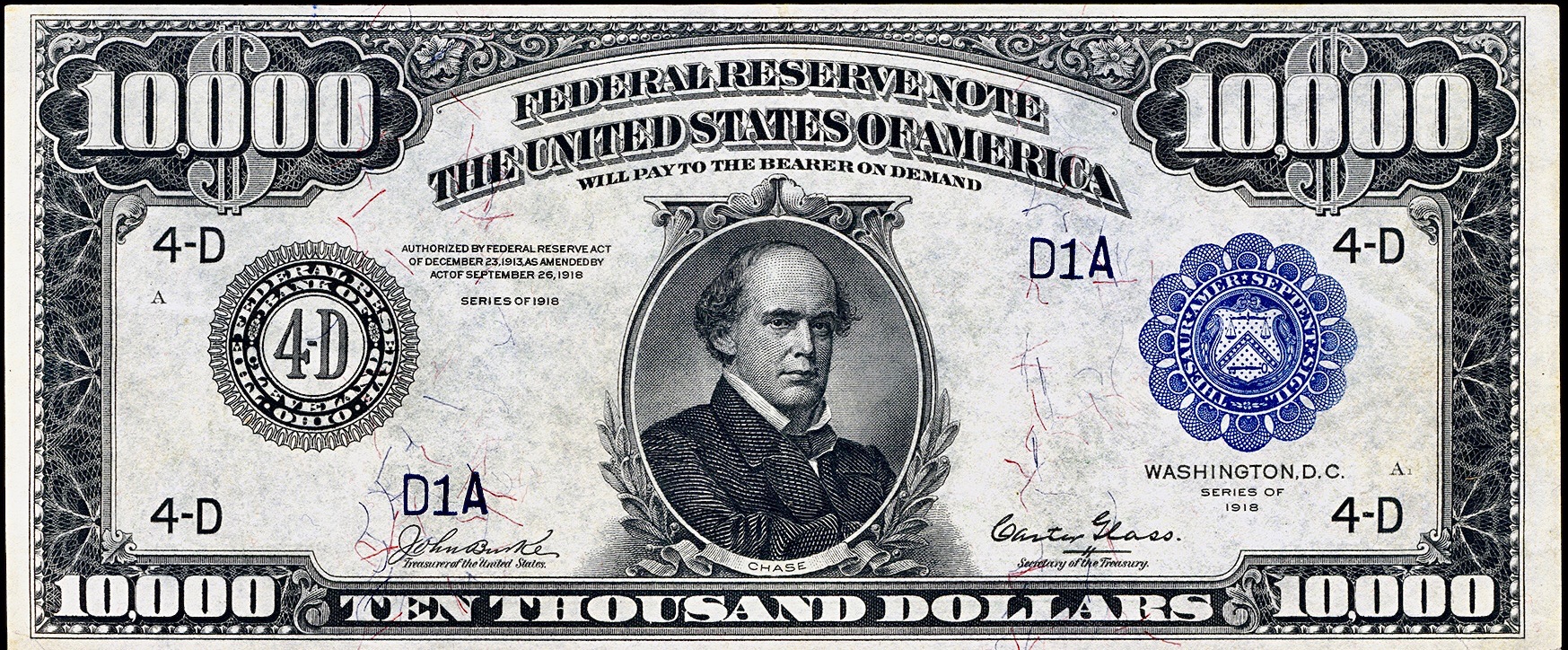

Imagine that a 15-year-old made a single investment of $1,000 and “let it ride” in an IRA (Roth or standard) until she was 65 years old. The money would double 10 times over the course of those 50 years. Simplifying this example to a “double” every 5 year: $1,000 at age 15 becomes $2,000 at age 20, $4,000 at 25, $8,000 at 30, $16,000 at 35, $32,000 at 40, $64,000 at 45, $128,000 at 50, $256,000 at 55, $512,000 at 60 and finally $1,024,000 at age 65! However, a delay of just 5 years at the start would reduce this portfolio by over half a million dollars.

The lessons are to start taking care of one’s 65-year-old self when one is as young as possible. Also, don’t rely upon a single investment deposit, but make a habit of saving. Pay “Uncle Sam” first, then pay your 65-year-old future self, and only then address current needs and “wants”. Investment planners often counsel that one should dedicate 15% of after-tax income to that long term horizon.

Of course, there are no guarantees. The market can swing wildly with years that are up and years that are down. Financial counselors warn to diversify one’s portfolio, include stocks, bonds, CD’s, etc.. My point is that we do our children and grandchildren a service by teaching the habits of saving and frugality at an early age. My oversimplification has ignored the basics that as one approaches retirement one’s investments should become increasingly more conservative. I do however want to make a few other points:

Do not save so obsessively that one sacrifices enjoying reasonable current rewards from the fruits of one’s labors. Saving for near-term goals is also important for mental health and personal satisfaction.

Work to achieve a shared financial partnership with your spouse. Talk about money and goals. Engage in shared decision making. Money disputes destroy more marriages than infidelity.

Don’t “react to the market”. This only encourages impulsive actions. I recall a friend sharing that when the market took a sudden downturn, more than 25% in a short period of time, he transferred his retirement account holdings from a stock mutual fund into a cash investment. He not only missed the near immediate market correction that followed but also the longer-term surge into a memorable stock market rally. He got “hit” twice, losing on the downturn and impulsively “choosing” to miss out on the rally.

Don’t pay too much attention to one’s portfolio balance. Train yourself to look at monthly and quarterly statements as if the bottom line is only a presentation of “numbers on a piece of paper”. As your portfolio grows seeing a swing in value of tens of thousands of dollars can feed panic or (just as bad), unwarranted exuberance. Panic can result in impulsive decisions as detailed above. Exuberance can cause one to (falsely) believe one has the expertise to “time” or “out-think” the market with consequences that can be equally disastrous.

Finally, convince yourself that the savings are not yours to spend, yet. With the success that disciplined saving achieves there will come a point where the account can deliver a shiny new car (or some other current “want”) that has become an obsession. Succumbing to the urge one will not only pay the price of the car, but the price of losing financial security later in life.

So, what brought all of these thoughts together and drove me to write this post? One of our children asked if there was information about investing that I could recommend for her to share with her children. Christine and I went online and bought copies of the book, “Investing for Kids” (by Redling and Tom, available on Amazon) for each family, along with a one-year subscription to Better Investing Magazine. We gifted those items to each family for Valentine’s Day.

In presenting these we engaged the 9 grandchildren who with the exception of a 3-year-old are all between the ages of 11 and 13 in a discussion. We shared our thoughts about money, saving, investing, and the future. It was a pleasant surprise that they paused television, put aside the electronics, and were interested, attentive, and engaged. It bodes well for their financial future and our peace of mind.

Peace Everyone. Pete

PS. A reality check. My “editor” (that would be my wife, Christine) asked me to consider the results if there were regular savings over 50 years without the 15-year-old having an initial $1,000 deposit. What would be the result if the deposits were much smaller but made consistently over time?

Here are just 2 scenarios that involve $100 per month (less than a pack of cigarettes or a Starbuck’s caffe latte a day) invested over those same 50 years:

- $100 per month over 50 years beginning at age 15 with interest growth at 12.96% (remember, the average growth of the S&P 500 from 1950 to 2020) grows to $4,312,833.00 at age 65! That’s over 4 million dollars!

- $100 per month over 50 years beginning at age 15 with a more conservative 9% annual rate of return still results in $1,025,254.00 at age 65. Over one million dollars.

It is human nature is forego saving for the distant future. After all, the challenge of today is what we face. Mine is an effort to express that today may offer us the best or only opportunities with which to provide for the welfare and security of the 65-year-old we will one day become.

Peace Everyone. Pete

**Note: In 1960 when Mr. Cruz arrived as a teenager in the United States, he spoke only Spanish. His family settled here in Kansas City Missouri where he attended Westport High School. In his December 10, 2010 column he expressed gratitude for teachers John Ploesser, Inez Pletcher and Thomas Sickling, each of whom he believed contributed to his adjustment and future success.